14th century BC Among the huge number of archaeological sites in the Romangia, remains were found of vases and wine pitchers.

10th century BC. Date of one of the very few intact askos vessels, found near Monte Cao in Romangia.

2nd century BC through 3rd century AD Dozens of wine amphorae testify to the Roman wine trade. Lying buried in the beach of Marina di Sorso at the La Varrosa nuraghe, they throw light on Roman wine production and commerce.

46 BC. Julius Caesar founds the first and only Roman colony in Sardinia, Turris Libyssonis, which includes the areas of Sorso, Sennori, and Castelsardo.

27 BC. In the hinterland of the Turris Libisonis colony, in “Romània”, numerous farms and rural settlements were founded, alongside many previously abandoned nuraghe, testifying to the development of an intensive agricultural economy, of the latifundia type, with huge capital investments directed predominantly to grain production on the plains near Alghero (Nurra) and towards Sassari. On the hillslopes of the Romània area, great emphasis was placed on enlarging and specialising vineyard and olive cultivation, contrary to the practice of the Carthaginians, who had concentrated on the production of beer rather than wine.

3rd through 7th centuries AD.On the coast of Marritza (Sorso), traces of foodstuffs, including wine, at the Roman villa of Santa Filicita attest to Roman commerce. Also found were remains from the Imperial, Vandal, and Byzantine periods.

Ca. 1140.Gonariu II of Torres, born Gonariu de Lacon Gunale de Thori (King of the Justice of Torres-Logudoro), gifted the Cistercian monks properties located in the Romangia, in the areas of Save, Osilo, Taverra, Septempalmas, and Enne. Rather than a simple donation, the gift was prompted by a choice of life-style, since Gonariu was acquainted personally with the founder of the Cistercian order, Bernard of Clairvaux. In fact, Gonariu transferred to his son the title of King of Torres and became a monk himself, moving to Clairvaux, in France, where he died in 1150. Bernard of Clairvaux founded the Cistercian order in the 12th century, with the Abbey of Cîteaux (1098) as its motherhouse. He imposed strict rules on the order, which alternated prayer and work. Under the Rule, the monks achieved significant results in improving their vineyards as well as their agricultural fields. They adopted novel winemaking practices and carefully preserved records of their experiments, and their research made possible the first viticultural zonation project in the history of wine. They controlled properties in Côte de Beaune and in Côte de Nuits, as well as in Chablis and Chalon-sur-Saône. Their labours and writings substantially contributed to the reputation and protection of the entire area of Burgundy, which included the vineyard of Romanée-Conti.

1101 through ca. 1300

Constantine de Thori I of Torres, as Protector of Romangia, authorised Giorgio Mugra to sell the vineyard of Gennor (a now-abandoned village in the Romangia).

Mariano de Thori, as Protector of Romangia, and before he became King of Logudoro, gave to Comita de Thori Gavisatu his domus (indicated a farm with extensive holdings) in Favules, with its servants, vineyards, fields, sheep, pigs, and all that he owned both within and beyond the domus.

As ex-King, he gave to San Pietro di Silki, a Church establishment, the domus of Gennor, with its servants, lands, and vineyards, as well as the saltu (fallow field) of Bubui, with a boundary amounting to hundreds of metres, alienated from the royal lands. The same field King Barisone II di Torres–Lacon de Thori—gave to his brother Comita de Martis.

The Cronaca Logudorese (Logudoro Chronicles), also known as the Liber Iudicum Turritanorum, refers to King Mariano I de Thori’s passion for wine, so immoderate that his mother had recourse to spells to keep him from it. In fact, he was “cured” of it, but he died nonetheless, according to the same source, allegedly from drinking too much (infected) water. Orunesu, Puxeddu 1993, pp. 32-35).

Comita de Thori Leriane and his wife Susanna de Thori gave the Church foundation San Pietro di Silki their fallow field in Urcone.

Mariano de Thori, for the benefit of the soul of his mother, his domus of Salvennor, together with its buildings, fallow and cultivated lands, vineyards, servants, as well as every asset he possessed, excluding those belonging to his paternal line.

1294. The Libero Comune di Sassari (Free Commune of Sassari) is established, which includes the Romangia. Sorso, Sennori, and Osilo become the District of the Città di Sassari (City of Sassari).

1300. Excavation in the pre-historic and later medieval village in the Geridu (Romangia) area brought to light remains of carbonised grape-pips, knives for pruning and harvesting, terracotta jugs used for wine-drinking, and wine-production containers.

1316. The Statuti Sassaresi (Sassari Statutes) were published in Sassari, one of Europe’s first civil and penal codes. The minutely-detailed regulations pertain to agriculture as well, above all vineyards and wine, among them one that prohibited the planting of new vineyards and the importation of wine, clearly signalling a desire not to harm a flourishing economy with increased production and wine availability. In addition to allowing the replacement of unproductive vines, the only exception granted to grapegrowers was the planting-out of un-planted areas in an already-established vineyard (“sa terra vacante intro dessa cuniatura dessa vigna sua). There were no restrictions placed on sought-after table grapes not on drying grapes in the sun (“tricla et simizante uva qui no se operat a binu”).

The importance of winegrowing for the local economy can be easily gauged by events that followed the 1329 insurrection led by the Pala and Catoni families against the Catalan-Aragonese authorities. Initially, the rebels were banished from the city and their assets confiscated, but shortly after, less severe attitudes prevailed, and the families were invited by the authorities to return to the district of Sassari to return their vineyards to production (“laurar e penjar les vinyes”), since otherwise the crops would have suffered.

1440. The Lord of the Romangia area granted exemptions to the inhabitants of Sorso and Sennori aimed at further stimulating viticulture (“specialmente in plantare vignas”); a body of rural guards was also established, whose task was to watch over the vineyards day and night. He also abolished the diritto d’uscita (“drittu de sa ixida,” or exit tax) imposed on those who went to purchase wine in the two towns.

1538. The coopers in Città di Sassari organised themselves into professional guilds as early as the 16th century; in Sassari, they were associated with the confraternity of fusters, picapedrers, sellers e bosters,whose founding statute dated to 1538.

1602. n the Pedraia area of the Romangia, archaeologists discovered a wine-making operation cut into the limestone rock, with the date 1602 scratched into a support.

1630. First written mention of Badde Nigolosu. The Amat archives in Cagliari contain the reference: “Sas terras de Badde Nigolosu. S.a Juanneddu Detori In sas terras de Murtedu.” (The lands of Badde Nigolosu.) (AAC, Amministrazione, n.27/1 1630).

1639. The Commune of Sassari set the price of a cask of Malvasia at 33 lire sarde, and of “vin blanc y canonat” at 18. The latter term is one of the first documented references to the wine produced from the famous Cannonau variety.

1677Franciscan monk Giorgio Aleo, diplomat of the King of Sardinia, wrote: “Los vinos son tintos y blancos y canonates [Cannonau], de color como rubi […], muy buenos generalmente en toda la isla , pero lo mas apreciados y regalados son los canonates, la garnacha, el girò, las malvasias y moscatos de Quarte y demas lugares de la comarca de Caller, de Sorso y Sennori, de Bosa y los vinos griegos de Lacono>>.” Quoted among the sources by the Disciplinare DOC Canonau di Sardegna. (DOC Canonau di Sardegna Production Code)

1746. The Treasury Minister of the Kingdom, Francesco Giuseppe de la Perrière, Count of Viry, drew up a lengthy historical-geographical report containing a very detailed description of rural Sardinia, once again describing a viticulture extremely widespread in various areas of the island. The territories in which winegrowing was particularly well-established were concentrated principally in three areas: the hinterland of Cagliari, the hills of Ogliastra, and the north-west corner of Sardinia. In northern Sardinia, viticulture was particularly important in the Romangia, in the Sassari district, and around Alghero. (“Le terroir abonde en vin, huille, blés et beaucoup de paturages.”) Bosa, farther to the south, on the western coast, had long enjoyed a reputation for its “excellente malvoisie.” Quoted among the sources by the Disciplinare DOC Canonau di Sardegna (DOC Canonau di Sardegna Production Code).

1776. Francesco Gemelli, in his 1776 three-volume Rifiorimento della Sardegna. Proposto nel miglioramento di sua agricoltura (Revival of Sardinia. Proposal for Improving its Agriculture) published in Turin, wrote, “I can only enthusiastically commend the inhabitants of Sassari, and in general all Sardinians, for the thoroughgoing diligence and exquisite attention they devote to cultivating their vines, and I believe that that sector of agriculture flourishes more than any other in the Kingdom, and therefore, nothing, or next to nothing, requires reform.” Regarding the wines, he wrote, “To be more precise, I distinguish three categories of wines in Sardinia: lightly sweet, powerful, and light and dry. The lightly sweet wines include Moscadello, commonly known as Moscato di Cagliari; Girò; Cannonau, also from Cagliari; Moscato d’Algheri; and perhaps one could claim Malvagia di Sorso, as well. Among the powerful wines are Malvagia di Cagliari as the most powerful of all, the most famous being that of Bosa, as well as those of Sorso and of Algheri as well; the Vernacce of Oristano and of Cagliari; and the red wines of Algheri and of Oliastra. Finally, in the category of dry, light wines, and therefore easier to promote,I include the wines of Sassari, when they are well-made. The wines of the first two groups, are said to be more similar to Spanish wines than to French, while the contrary is true for the third group, which are closer to the French style and can contend with them, provided that responsibility is assumed of correcting their defects, which the majority of producers display, either in the wines’ manipulation or storage; the majority of Sassari inhabitants should follow the lead of a lesser number of their fellow citizens in foreswearing such wines.” Quoted among the sources by the Disciplinare DOC Canonau di Sardegna (DOC Canonau di Sardegna Production Code).

1777. The rural uprising against the feudal overlords broke out, particularly in the north-western parts of the island, and with particular virulence in Sorso and Sennori. The latter were, in fact, among the most-advanced towns of the island from the point of view of agricultural development, having adopted intensive systems of innovative, specialised cultivation in viticulture, fruticulture, and—since the 1600s—in oliviculture. (Doneddu-1990)

1780. Manca dell’Arca, in his 1780 tract Agricoltura di Sardegna published in Naples, offered “a detailed description of the grapes present in the area of Sassari, which included muscadelle, a soft, early-ripening grape with rounded berries (the current moscadeddu); coscusedda, with rounded berries (current vermentino); granazza, or garnaccia, with long, large berries; and cannonadu biancu. The dark grape varieties include zirone, a soft,early-ripening grape with rounded berries; zirone di Spagna, with larger rounded berries; muristella, late-ripening, with dense-packed, rounded berries; pascale: ith large, rounded berries in a large cluster; redagliadu Nieddu, with dense-packed, large, rounded berries; and cannonadu, with somewhat rounded berries. (Note: retagliadu Nieddu is the ancient clone of cannonau present only at Sorso Sennori.) Quoted among the sources by the Disciplinare DOC Canonau di Sardegna (DOC Canonau di Sardegna Production Code).

1820. Vittorio Angius collaborated on the monumental work, Dizionario geografico-storico-statistico-commerciale degli Stati di S. M. il Re di Sardegna,1833-56 (Commercial, Statistical, Historical, and Geographical Dictionary of the Royal States of Sardinia), an extremely detailed description of every village on the island. Regarding the Romangia, he wrote: “The vineyards here flourish splendidly and produce excellent-quality wine and table grapes. There are more than twenty grape varieties, between red, black, and white. The amount of wine made from black and white grapes, from everyday to premium quality, is enormous. Worthy of note among the premium-grade wines is Malvasia, inferior to none other on the island, particularly when aged a few years. Although a prodigious amount is consumed locally, a large quantity is nevertheless purchased by the Genoese, at 50 soldi (2.50 lire) per 80-litre cask, when the market is good.” Quoted among the sources by the Disciplinare DOC Canonau di Sardegna (DOC Canonau di Sardegna Production Code).

1887. Cettolini remarks, in his Elenco delle principali uve sarde (List of Principal Sardinian Grapes), that this grape was also known as Cannonatu in Tempio and Retagliadu nieddu in Sorso. (Quoted among the sources by the Disciplinare DOC Canonau di Sardegna (DOC Canonau di Sardegna Production Code.)Bruni (1952-1960) completed the grape’s ampelographic catalogue with a description of its phenology, characteristics, growth behaviour, and utilisation, and reported that in 1951 Cannonau was widely planted throughout the island and constituted the predominant grape in Ogliastra and around Sorso. Quoted among the sources by the Disciplinare DOC Canonau di Sardegna (DOC Canonau di Sardegna Production Code.)

1960. “Ampelographic Technical Sheet in the National Register of Italian DOP and IGP Winegrape Varieties,” under the supervision of the Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies: <<“The first to refer to it was Manca, who called it Cannonadu. Acerbi referred to it as Canonau and Moris as Cannonau, classifyng it as Vitis praestaus nigra, and Baron Mendola referred to Cannonadu nieddu, Canonao, Cannono. The Bollettini ampelografici (Ampelographic Bulletins) describe it under the names of Canonao, Cannona; page 76 reads: “according to the notes supplied by Prof. Nicola Meloni, it corresponds to Spain’s Alicante and to the Grenache of France,” while on page 90, stated that “it is identical to the Granaxa of Aragon and to the Grenache of the French.” It is also known as Cannonaddu, Cananao. And, according to Cettolini, Cannonatu in Tempio and Retagliadu Nieddu in Sorso. At times, mixed in among the other vines, one comes across a clone known as Cannonao bastardu or Cannonau selvaggio, quite vigorous, with a loose cluster due to autosterile flowers.>.

1961. Giuseppe Dessì quoted in I Vini d’Italia (The Wines of Italy), by Luigi Veronelli in 1961, stated: <<Every Sardinian tries to overcome this atavistic distrust of the spoken word with the help of a glass of wine. When one drinks among friends, wine restores warmth and friendship. All those who have been our hosts in Sassari, in Nuoro, in Oristano or in Quarto, or else in Alghero or in Sorso, in war and in peace, realise how important it is for a Sard to drink in company, and how much effort it costs. It’s like holding oneself well in the saddle for one not accustomed to riding. I’m talking here, of course, of wines of breed—of Girò, of Moscato del Campidano, of Malvasia di Bosa, of Vermentino di Tempio, of Nasco, Monica, Oliena, I’m speaking of Torbato d’Alghero, of that profound, metaphysical Moscato di Luras, of that noble, generous Cannonau di Sorso. And I am speaking above all of Vernaccia.>.

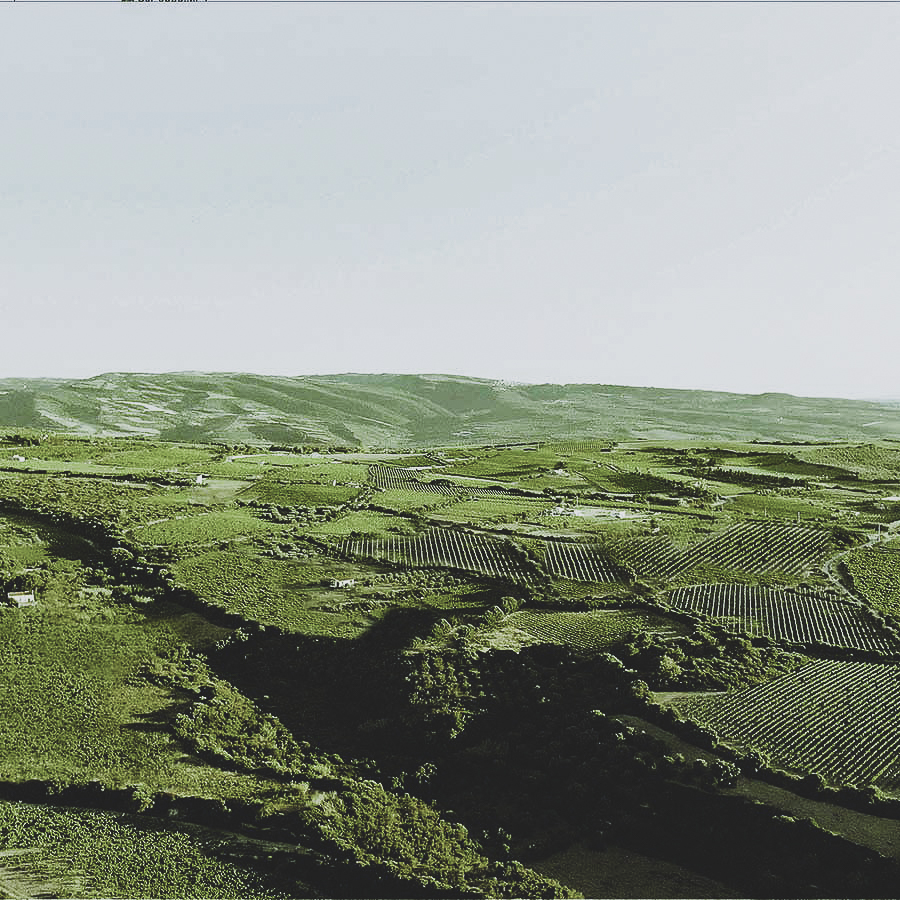

2015. ISPRA-Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (The Higher Institute for Environmental Protection and Research) stated in 2015, in its Quaderni Natura e Biodiversità (Nature and Biodiversity Notebooks),<< Thus, the vineyard landscape varies in accord with the specialisation of the growing area, with cultivation approaches, and with winegrowing traditions. In the Sassari area, it is worth note that the Romangia landscape exhibits the signs of a traditional viticulture still based on vine training to the alberello method. The agrarian countryside is characterised by small vineyards alternating with olive groves that stud the limestone hillslopes of Sennori and Sorso, stretching as for as the sandy soils on the plain at Marina del Sorso and along the coast towards Badesi. The most widely-planted varieties are Cannonau and Moscato, while Taloppo is the predominant table grape, with a minor role are played by Vermentino, Pascale, and Bovale sardo.>>